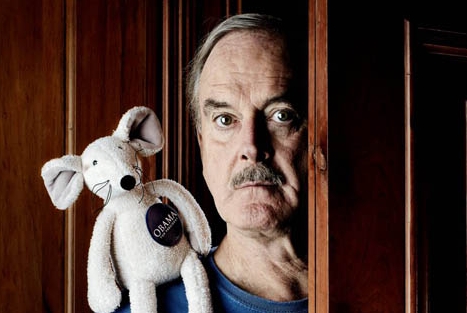

It’s fair to say that John Cleese is quite bitter when it comes to his ex-wife. The first ten minutes of his one man show – The Alimony Tour – is a vicious rant about their marriage and the outrage of being ordered to pay her £2 million by L.A. judges. This is why, we are told, he is forced to travel the country showing clips of his past glories and regaling audiences with anecdotes about the desperate nature of Weston Super-Mare, how he once told his mother he could hire an assassin to kill her and Graham Chapman’s habit of biting folks’ ankles at BBC cocktail parties.

It’s fair to say that John Cleese is quite bitter when it comes to his ex-wife. The first ten minutes of his one man show – The Alimony Tour – is a vicious rant about their marriage and the outrage of being ordered to pay her £2 million by L.A. judges. This is why, we are told, he is forced to travel the country showing clips of his past glories and regaling audiences with anecdotes about the desperate nature of Weston Super-Mare, how he once told his mother he could hire an assassin to kill her and Graham Chapman’s habit of biting folks’ ankles at BBC cocktail parties.

The vitriol that Cleese pours on his wife and her lawyer (who is compared, in complexion to an Orc) is vindictive, uncomfortable and absolutely hilarious. His diatribe almost reduced me to tears, although another punter, two seats down, wasn’t enjoying it so much. There was much sucking of air through teeth and tut-tutting. For this gentleman, the breakdown of a marriage was not a laughing matter.

As you’d expect from a Python, Cleese returned to the concept of black humour. Why, he asked, do hard-edged jokes get a bigger laugh from audiences? He revealed that after test screenings of a Fish Called Wanda the test-audiences had been asked for their three funniest moments in the film. The results were:

- The dogs being killed.

- Michael Palin’s character being tortured with an apple and some chips.

- John Cleese prancing about in the nude.

They were also asked to list the sequences that offended them the most. They chose:

- The dogs being killed.

- Michael Palin’s character being tortured with an apple and some chips.

- John Cleese prancing about in the nude.

So why do we cry with laughter at the things that offend us? The obvious answer is that we know we shouldn’t. There are taboos that we know shouldn’t raise a titter: religion; illness; sexuality; and death. Yet, these are the jokes that produce the largest belly laughs. As Cleese says, there is an inherent anxiety wrapped up in such subjects and guilt that we shouldn’t find them funny at all. But, when you realise that other people are also tickled by them, the laugh gets bigger. Perhaps it’s the relief that you’re not a moral deviant?

The same goes for horror movies. A while ago I was working on marketing ideas for the Saw films. I showed the team the infamous bear trap sequence from the first movie. People laughed. Granted it wasn’t a full-on gaggle of guffaws, but a ripple of nervous giggles. Not one of them thought dismemberment or torture was humourous, but it was a way of dealing with what they were seeing.

I’d be interested in hearing what you think. Why is black humour so appealing? Is it the knowledge that we’re being inherently naughty, tittering away like school-children, or is it a defence mechanism, a way of coping with some of the darkest aspects of human life?

Be the first to comment